Part II: Theological Horror: Stories that Make Us Sadder and Wiser

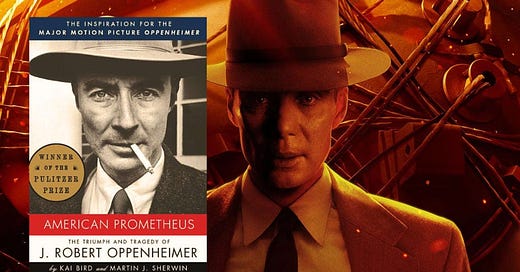

Oppenheimer, Prometheus, John Donne

Welcome to The Empathetic Imagination! This newsletter was born out of my interest in the relationship between the arts and spiritual formation, particularly the cultivation of empathy (which also led to my book). In this weekly newsletter, we will look at the connections between art, theology, and the hard work of being a loving, truthful human being. Thank you to all who subscribe, especially those who have opted for a paid subscription. This helps me to continue to do this work! Along with writing on the arts and theology, I will be offering some (non-credit) go–at–your-own–pace courses on these topics for paid subscribers.

Hello, friends!

Last week, we looked at Frankenstein, The Rime of the Ancient Mariner, and the myth of Prometheus as works of theological horror. If you missed it, you can read HERE.

This week, we will relate the same theological theme–the spiritually corrosive power of pride and power–to the film Oppenheimer, the myth of Prometheus, and “Holy Sonnet IV” by John Donne. Instead of writing about Breaking Bad this week, I have decided that there needs to be a PART III to this series. So stay tuned next week!

Unlike Shelley’s Frankenstein, Christopher Nolan’s Oppenheimer does not appear to be overtly and intentionally theological in its message (in the sense that he does not spell this out as Shelley does). At the same time, Nolan’s depiction of J. Robert Oppenheimer’s story has much in common with Mary Shelley’s poignant dream description of Victor Frankenstein’s reaction to his act of creation:

“Frightful must it be; for supremely frightful would be the effect of any human endeavour to mock the stupendous mechanism of the Creator of the world. His success would terrify the artist; he would rush away from his odious handywork, horror-stricken.”

Perhaps those who have seen Christopher Nolan’s epic biopic Oppenheimer recall these lines written in the opening sequence:

“Prometheus stole fire from the gods and gave it to man. For this he was chained to a rock and tortured for eternity.”

The film’s title and the reference for this quote both come from the title of the Pulitzer prizewinning biography American Prometheus: The Triumph and Tragedy of J. Robert Oppenheimer by Kai Bird and Martin J. Sherman. Actor Cillian Murphy’s depiction of the determined, tragic figure with seemingly unearthly intelligence is a continual reminder of Shelley’s own Prometheus references. On the simplest level, we see Oppenheimer as a man with an almost monomaniacal obsession with creation of something that leads not to life, but to destruction. He longs for the creation of decreation. It is a prideful privilege that the creator of this grand weapon of destruction does not really anticipate its consequences.

After the success of the Trinity Test on the first atomic bomb, Oppenheimer famously recalls the reactions of his co-laborers alongside a quote from the Bhagavad Gita:

“We knew the world would not be the same. A few people laughed, a few people cried. Most people were silent. I remembered the line from the Hindu scripture, the Bhagavad-Gita; Vishnu is trying to persuade the Prince that he should do his duty, and to impress him, takes on his multi-armed form and says, 'Now I am become Death, the destroyer of worlds.' I suppose we all thought that, one way or another.”

This interesting article by James Temperton explains the context of the lines, 'Now I am become Death, the destroyer of worlds,’ in the original text, highlighting their connection to the elevated mindset of a warrior preparing for battle. In Nolan’s film, Oppenheimer is also portrayed as one who is creating (or acting) evil to abolish an even greater evil: “I don't know if we can be trusted with such a weapon. But I know the Nazis can't.”

Cillian Murphy’s depiction of the “American Prometheus” is complex and deeply human. Like Prometheus and Victor Frankenstein, Murphy’s Oppenheimer “steals” knowledge that no human being should be able to access: the secret of annihilation. He is so driven by an abstract mission to destroy the “greater evil” that he does not recognize the spiritual damage he will incur after creating a tool to destroy masses of (what I see as) image bearers. After Oppenheimer learns of the impact of his handiwork, the film powerfully illustrates recurrent electrical flashbacks–envisioned melting faces and screaming cries of the residents of Hiroshima and Nagasaki–that haunt him. His project is no longer a theory but a life-altering lived reality: “They won't fear it until they understand it. And they won't understand it until they've used it. Theory will take you only so far.”

As Francis Schaeffer once wrote, “Ideas have legs.” And in this case, the manifestation of abstract theories shocked its very creator, perhaps echoing Shelley’s lines: “His success would terrify the artist; he would rush away from his odious handywork, horror-stricken.” As with Prometheus and Frankenstein, the devastating impact of Oppenheimer’s creation is ever-present, causing pain, fear, and regret. When the beleaguered Oppenheimer visits President Truman after the bombs have been dropped in Japan, he confesses “Mr. President, I have blood on my hands.”

In this regard, it is fascinating that (the real) Oppenheimer named The Manhattan Project’s first atomic test bomb “Trinity” after quoting the opening lines to the famous Donne poem: “Batter my heart three-person’d God.” In this poem, Donne describes the paradoxical nature of the human condition; the speaker both hates his and God’s enemy (Satan) yet is “betroth’d” to him. As much as he tries to “divorce” himself from the seduction of the evil one, he must ask God to violently break him–"batter” his heart–for him to be humbled and saved from his own desire toward destruction.

Donne’s poetry (this poem and others) portrays the human condition as “inconstant,” to use a word from philosopher Blaise Pascal. Both Pascal and Donne illustrate the wrestling of flesh with spirit, the dual nature of a human being as both made in God’s image and woefully fallen. In Pensées, Pascal describes the tension between the greatness and the wretchedness of the paradoxical human condition, emphasizing the “tangled knot” of human anthropology:

“What a novelty, what monsters! Chaotic, contradictory, prodigious, judging everything, mindless worm of the earth, storehouse of truth, cesspool of uncertainty and error, glory and reject of the universe.”

The genius of Christopher Nolan’s film lies in his portrayal of Oppenheimer– not as a villain or a hero–but a brilliant, tortured human being “the glory and reject of the universe.” The Donne poem, echoing Pascal’s (biblical) ideas about the human condition, explains that the reality of human existence is not black or white: a person is never fully good or fully evil. Interestingly, Nolan’s Oppenheimer only develops a conscience once he is broken by the evil impact of his own creation (hello, Victor Frankenstein!). In Donne’s Holy Sonnet IV, the speaker begs God to use His force to “break, blow, and burn” him in order to make him “new.” Only after a sort of holy destruction can he be redeemed. In Oppenheimer’s case, his breaking is more of a Romans 1 sort, the pain of being left to one’s own devices, the “freedom,” to destroy oneself and others. Once Oppenheimer sees that his “odious handiwork” has landed him with a “godlike” ability to brutally destroy thousands of civilians, he is terrified and humbled.

In the description of The Meanings of J. Robert Oppenheimer, Lindsey Michael Banko writes of the public and historical interpretations of Oppenheimer, the man and historical figure:

“In the decades since the successful detonation of the world’s first atomic bomb under his supervision, Oppenheimer has been portrayed as an emotionless and soulless man of science, an almost mystical Byronic visionary, a popular celebrity, an incarnation of the horrors of nuclear warfare, the embodiment of the American dream, and a Communist threat to the American way of life.”

Nolan’s Oppenheimer is a man with a soul, and that is why this film is a masterpiece. Neither villain nor hero, Oppenheimer is portrayed as a man weathering the deathly storms of his own making. In the third part of the film when we see him sitting through a seemingly makeshift “trial” concerning his security clearance, Oppenheimer’s countenance has sunken. His tall, thin body is no longer masterful but gangly and sad. His eyes carry the weight of the world as he is humbled by the devastation of his own power.

Like reading Frankenstein and The Rime of the Ancient Mariner, watching the story of Oppenheimer’s redemptive demise on the big screen can make us both sadder and wiser. We see the impact of following our unchecked passions and being blind to consequences. Both of these actions are a form of playing God, chasing and harboring the sin of pride. Once we see it within another, we recognize it within ourselves. We are wiser but also sadder as we know we must be more attentive to our behavior, more sacrificial in our dealings with others, more humble as we seek God.

Thanks for reading, everyone.

I want to mention a few things before I sign off. I just saw that my book is currently on sale at Amazon for $11.52!

Here are a few review comments from authors you might know:

"Imagining Our Neighbors as Ourselves will instruct and delight any reader who cares even a little about art, imagination, and humanity." --Karen Swallow Prior, author of On Reading Well and The Evangelical Imagination

"From Douglas Coupland to C. S. Lewis, from Flannery O'Connor to Toni Morrison, McCampbell paints a landscape of mystery, hope, and splendor for our imagination to be fed and to be nurtured toward the New Creation." --Makoto Fujimura, artist and author of Art+Faith: A Theology of Making

"McCampbell takes the ingredients of the familiar and invites us on a theological and experiential journey to self and neighbor compassion. In her book, both storytelling and story analysis, from film to Holy Scripture, inspire and equip us to grow what seems so lacking today: empathy." --Christina Edmondson, psychologist, cohost of the Truth's Table podcast, and author of Faithful Antiracism: Moving Past Talk to Systemic Change

"McCampbell has given us a vision of a flourishing community: one full of art, music, film, and fiction that tells the stories of who we are and the diverse gifts we bring to the table." --Jessica Hooten Wilson, author of The Scandal of Holiness and Reading for the Love of God

Don’t forget that PAID subscribers will be able to join me for an online class starting Feb. 19! I will be posting a film selection soon. More info HERE.