PART I: Theological Horror: Stories that Make us Sadder and Wiser

Part I: Frankenstein, Prometheus & the Ancient Mariner

Dear readers,

I am delighted that there are so many new subscribers to this newsletter! Thank you so much! Today’s letter focuses on themes of theological horror in Romantic literature, especially Frankenstein. In the next newsletter, I will continue the theological discussion but relate it to television and film. From February-May, my letter’s main focus will be film. So I am glad to send you a lengthy literature-focused post today. Let’s go ahead and dive in!

FRANKENSTEIN

In the author’s introduction to the 1831 edition of Frankenstein, Mary Shelley describes her vivid nightmare of a maniacally obsessed scientist’s (un)successful attempt at recreating human life. The dream was influenced by midnight conversations between her husband, Percy, and other literary figures, including Lord Byron, to which she was “a devout but nearly silent listener.” On one occasion, the discussion focused on the seemingly miraculous “involuntary movement” of a vermicelli noodle that Dr. Erasmus Darwin–grandfather of Charles–had been preserving in a glass case. The mind of teenage Mary Shelley became fixated on this example of bringing supposed “life” to something lifeless, wondering even if human life could be replicated from inanimate matter, including dead bodies (what a jump!). Mary famously relayed the chilling details of her dream as an entry to Lord Byron’s ghost story contest. The rest is literary history.

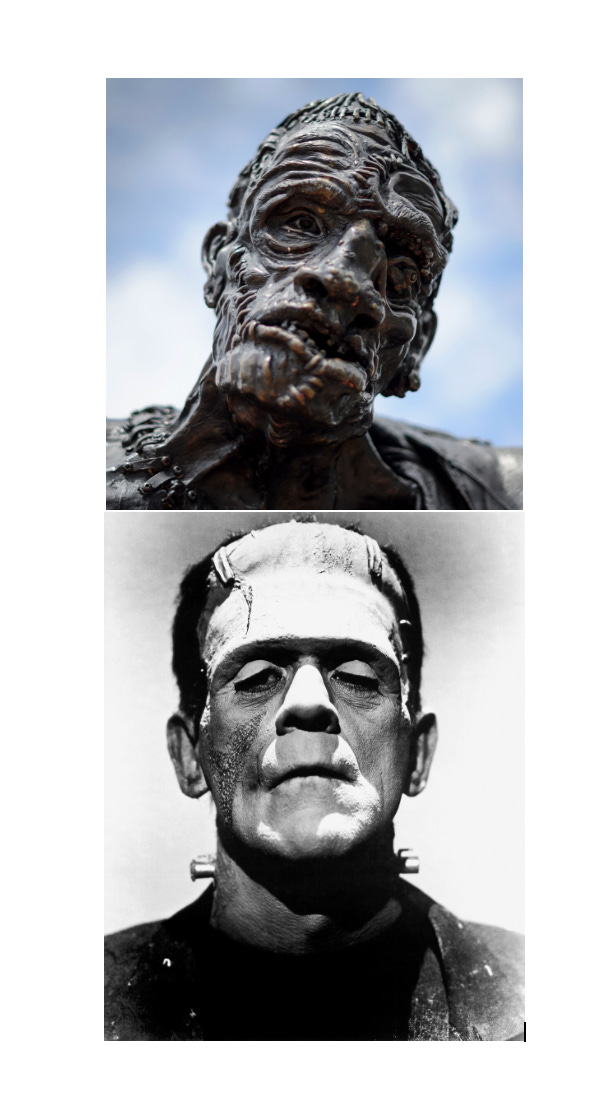

Shelley’s brief description of the most disturbing part of the dream does not include any Hollywood-esque violence and bloodshed. There is no description of a grunting square-headed green man with a bolt through his neck. This is not Mary Shelley’s sort of horror. In the photos posted above, just look at the difference between the almost comical Hollywood caricature of the Frankenstein monster (bottom) compared to a statue in Geneva (top) of the novel’s tortured, unnamed creature. Shelley’s focus in the novel’s introduction–and throughout the novel–is much less on body horror than it is on internal theological horror. The Geneva sculpture pictured above could be a depiction of the creature’s frightening external appearance or of the chaotic, twisted internal landscape of his creator. The most horrific transformation in the novel is not the creation of a living being out of dead flesh but the spiritual corrosion that occurs because of Victor Frankenstein’s prideful act:

“Frightful must it be; for supremely frightful would be the effect of any human endeavor to mock the stupendous mechanism of the Creator of the world. His success would terrify the artist; he would rush away from his odious handiwork, horror-stricken.”

Victor’s ill-fated attempt to gain secret knowledge and create something in his own image uncovers the distorted, decayed, malicious parts of his own darkened soul. In this story of the fatal impact of pride and the claustrophobic, antisocial isolation of sin, the scientist and his creature begin to resemble each other more and more. Both have been deeply damaged by their acquisition for knowledge, but their reasons for seeking information are very different. The creature is like a child abandoned by his parents, left alone in the world with little or no understanding of humanity, morality, and the natural world. He seeks knowledge in the way that a child does, and his appetite is voracious. After learning to read by watching the family whose hovel he is inhabiting, the creature finds and reads Paradise Lost and recognizes that he should be like Adam, but because of his creator’s abandonment, he became more like Satan. In reading and realizing this–while being violently rejected and abused by all humans he encounters–he declares that “sorrow only increases with knowledge.” The more he learns about his misfit status in the world and of “man’s inhumanity to man,” the more he hates himself and the humans that fear him. Shelley’s creature is very human, perhaps even more human than his creator. It is much easier to empathize with the childlike monster than with Victor Frankenstein. This is especially true when contemplating why Victor–like his creature–has a passion for knowledge. The only reasons seem to be self-serving, to increase in his own eyes and in the eyes of others.

Victor and his creature both dwell on the very edges of society. Although Victor chooses this because of his selfish focus on “creation,” the creature is forced to live outside of any community. While both characters are foils to one another, their lives and behavior also parallel one another. This was brilliantly performed in a recent National Theater (UK) performance in which the actors Benedict Cumberbatch and Jonny Lee Miller alternated playing Victor or the Creature every other night of the show’s run (pictured above). In the novel’s second half, the creature–like his creator–has developed an all-consuming obsession with revenge. Both figures are transformed into monomaniacs, living for one thing only–a nearly Nietzschean focus on their individual wills crushing the life power of the Other.

In Mere Christianity and elsewhere , C.S. Lewis argues that pride is the original sin of humanity: “Pride is spiritual cancer: it eats up the very possibility of love, or contentment, or even common sense.” We clearly see this in Shelley’s novel as the brilliant Victor Frankenstein makes insanely unwise choices, isolates himself from his family and friends, and lacks any sort of contentment until he completes his diabolical mission. But in retrospect, Victor sees that he was “enslaved” to his sin, that he lacked any real freedom. Frankenstein continually reminds us that complete freedom is actually self-desctrucction; there must be some holy parameters. The theological impetus of the novel repeatedly points back to the biblical narrative of the fall of humanity. The (anti)-Edenic desire for godlike knowledge led to discontentment, lack of love (“the woman made me do it!”), and the absence of common sense. Victor’s desire to pick the apple from the tree of knowledge leads to his creature’s demise, and the abandoned creature’s transformation is spiritually fatal. The creature’s soul glowed with benevolence” but soon morphs into the soul of a “daemon” whose evil becomes his only good (paraphrase of the lines that Shelley directly quoted from Milton’s Satan). The sins of the (quasi)-father come down upon the (quasi)-son.

THE MYTH OF PROMETHEUS

Victor’s pride goes before his own fall, but also the fall (deaths) of many of his family members. His sin continues to breed sin, and he is constantly tormented both psychologically and spiritually by the vengeful threats of his own creation. The subtitle for Frankenstein is, fittingly, The Modern Prometheus. Perhaps you remember the Greek myth of the Titan, Prometheus, who stole fire from Mount Olympus and gave it to human beings (thus creating “civilization). Interestingly, he is also sometimes credited with creating human beings from clay. Zeus punished Prometheus because he, like Frankenstein, overstepped his boundaries and stole the secret of the gods. Prometheus’s punishment from Zeus is both physical and psychological as he is chained to a rock, waiting for a daily visit from an eagle who rips open his flesh and tears his liver out. The skin grows back just in time to be ripped out by the eagle after its regeneration. Prometheus’s pained anticipation of the torture is perhaps worse than its physical manifestation. Frankenstein’s constant fear of his creature’s next devilish turn creates anxiety and isolation that parallels that of Prometheus.

A Critique of Romantic Passion & The Rime of the Ancient Mariner

Even the narrative structure of Frankenstein references a theological horror that results from hubris. Shelley’s novel is actually a set of letters from a man named Robert Walton to his sister in London. Walton is an explorer whose obsession with “discovering” uncharted territory parallels Victor Frankenstein’s obsession with using “natural philosophy” to bring life from death. Walton’s shorter letters to his sister frame the narrative, and the pieces begin to come together for the reader when he sees the hazy shape of a large, unidentifiable creature on a sled. Days later, an emaciated, terror-stricken man appears at his (very remote) door. This, we learn, is Victor. He has come to the North Pole to find the creature and avenge the deaths of his family members. But upon meeting Robert Walton, his “mission” takes on a deeper, perhaps even redemptive, meaning. When Victor sees the same destructive flames of conquest flickering in Walton’s eyes, he exclaims:

“Unhappy man! Do you share my madness? Have you drunk also of the intoxicating draught? Hear me; let me reveal my tale, and you will dash the cup from your lips!”

Frankenstein is a novel exposing the parallels of human forms of sinfulness. Victor sees his younger, naive, and prideful self in Walton’s eyes and feels compelled to tell hi story, the novel’s longest letter. As much as this story is gripping and entertaining, it is even more a parabolic. This is especially fascinating considering how Mary Shelley was married to Percy, a poet who, along with Lord Byron, is grouped in the “Satanic School” of Romantic literature. Although Percy’s poems do not describe the corrupting influence of power as offenses to God (he was an atheist), he did see that a lust for power is morally damaging. Unlike William Blake, the first well-known Romantic poet, both Mary and Percy (as evidenced in “Ozymandias,” which will be discussed in the next newsletter) do not laud the act of following one’s passions no matter the cost. In The Marriage of Heaven and Hell, Blake’s Satan (considered a heroic figure, the great poet), sees putting limits upon human desire as the only real sin: “"Sooner strangle an infant in its cradle than nurse unacted desires."

In Frankenstein, Shelley shows us that the complete freedom of following one’s passions can leave to spiritual and psychological slavery. This creative critique of a major Romantic tenant is shared by another of Mary Shelley’s contemporaries, poet Samuel Taylor Coleridge. At the beginning of this section, I argued that the framing structure of Frankenstein is, in itself, referencing the idea of theological horror that results from hubris. This is because Shelley seems to have borrowed the narrative structure of her novel from Coleridge’s “horror” poem “The Rime of the Ancient Mariner.” The poem uses a framing narrative in which a “wedding guest” at a reception on a boat relays an eerie story told to him by an “ancient mariner,” a man who seemingly cast a spell upon the poem’s anonymous author. Like Frankenstein’s story, the ancient mariner’s story is not told to us directly. On one level, this cold, fantastical poem is about the importance of telling a story for the sake of spiritual and moral formation. In the story that the mariner tells to the wedding guest, he recalls his youth as a seaman. On one journey to sea, his boat and crew weathers a terrible, overpowering storm. After the storm had cleared, a large and beautiful albatross flies over the boat. Although this glorious creature is seen by the crew members as a good omen, the mariner takes his crossbow and shoots it. The poem provides no sound reason for the shooting; the mariner only shoots the albatross as a means to exert his power. He does it simply because he can. After this reckless destruction of nature–something that Coleridge treats as an offense to God–the mariner is mightily cursed. His crew members die, but the real terror occurs when they rise up as ghosts to haunt him. The poem is long, trippy, and mystical–you can read it all here.

Like Shelley, Coleridge’s focus is on the theological horror that manifests as the end result of mocking God and his creation. In the North Pole sections of Frankenstein, Robert Walton mentions the Coleridge poem directly multiple times, writing to his sister:

“I am going to unexplored regions, to ‘the land of mist and snow,’ but I shall kill no albatross; therefore do not be alarmed for my safety or if I should come back to you as worn and woeful as the ‘Ancient Mariner.’

Unlike Shelley, Coleridge create space for redemption. The mariner wears the dead albatross around his neck as a kind of penance, and then he begins to bless the natural world around him and regain an ability to pray.

The poem ends like this:

He prayeth best, who loveth best

All things both great and small;

For the dear God who loveth us,

He made and loveth all.

The Mariner, whose eye is bright,

Whose beard with age is hoar,

Is gone: and now the Wedding-Guest

Turned from the bridegroom's door.

He went like one that hath been stunned,

And is of sense forlorn:

A sadder and a wiser man,

He rose the morrow morn.

Both the wedding guest in “The Rime of the Ancient Mariner” and Robert Walton in Frankenstein are stunned into a state of sadness that follows newfound wisdom. Once again, “sorrow increases with knowledge,” but this is a redemptive, necessary increase. It is an increase of spiritual richness, greater empathy for humanity, and the will to change. To learn the story of another whose sin looks so much like ours is saddening– we see the impact and know we have to change. But the wisdom that comes from this sadness is life-giving.

Check back on Friday for PART II of “Theological Horror: Stories that Make us Both Sadder and Wiser.” We will be looking at the film Oppenheimer.

In my last newsletter, I provided some information about an upcoming class I will be teaching via this newsletter called “Theology and Philosophy in Film.” I hope you will join me for it! Find more info HERE.

I hope you enjoyed this newsletter! If you did–and you want to support my writing–please consider a paid subscription for just $5 a month!

I would love to hear your thoughts about these observations on theological horror in Romantic literature! I would also like to know if you have read Frankenstein and if you are as big a fan of it as I am!

Thanks for reading!

Mary