We Wear the Mask: Childish Gambino’s Satirical Inheritance

Another one from the archives. Sadly, it is still very relevant.

Welcome to The Empathetic Imagination! This newsletter was born out of my interest in the relationship between the arts and spiritual formation, particularly the cultivation of empathy (which also led to my book). In this weekly newsletter, we will look at the connections between art, theology, and the hard work of being a loving, truthful human being. If you appreciate my writing, consider buying me a cup of coffee (one time gift) or becoming a monthly subscriber!

My analysis below of the brilliant video for Childish Gambino’s 2018 song “This is America” is about so much more than the song and video itself. It places it in a prophetic tradition of critique and lament in the face of normalized injustice (and points you to multiple great works from that tradition). Oh, how much we all still have to learn from the Black tradition of hopeful yet critical and bold resistance. This article was originally published in the online magazine for The Witness: A Black Christian Collective. The magazine is no longer online, so I want to share this piece on my own Substack. And I also want to encourage you to check out and consider supporting The Witness Ic.

Childish Gambino’s “This is America” is a powerful, prophetic critique of the dehumanization and moral corruption that is often normalized in American culture. The shocking video for the song is brilliant. But it is nothing completely new.

To say that this video is “nothing new” is not an insult—it’s an acknowledgement of the rich tradition of African American art that both exposes and laments the ways in which a pervasive and widely accepted white supremacist mindset forces Black Americans to wear masks– to dance, to shut their mouths, and to and merely entertain. Glover has certainly mastered this clever, convicting approach to satire. Taking time to look more closely at his predecessors will help us to better understand his brilliant video and the conditions that led to its creation.

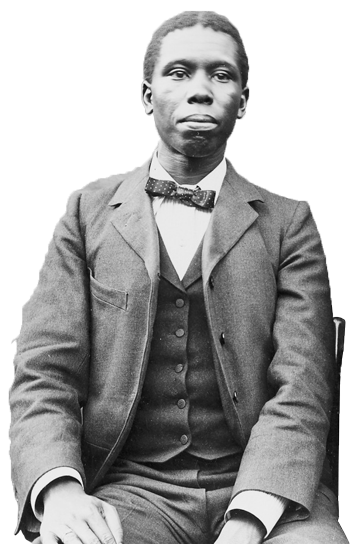

In his excellent piece on “This is America,” Andre Henry effectively argues that “This is America” is a “piece of art” that “recalls a tradition of frustrated messengers, grabbing a society by the collars and trying to shake it awake by any means necessary.” In this insightful comment, Henry is speaking of the ways in which the biblical prophets did “reactive, dramatic, offensive, and important” things in order to subvert the status quo and expose societal sins that needed to be redeemed. I also see African American artists such as Paul Laurence Dunbar, Lorraine Hasnberry, Eldridge Cleaver, Lupe Fiasco, and Spike Lee as those frustrated messengers, taking on the role of the prophet who speaks to a culture that, largely, did/does not have eyes to see or ears to hear.

Paul Laurence Dunbar’s famous 1913 poem “We Wear the Mask” explains that in white supremacist culture, “We wear the mask that grins and lies…with torn and bleeding hearts we smile.” Dunbar and his contemporaries knew that, although technically “free,” they were still seen as only partially human, tools for increasing white wealth or children to be disciplined. This dehumanization forced them to hide away the complexity of their humanity—the all too human anger, grief, and pain, in order to pretend that things are fine. They must work and they must entertain. The only space for solace is in the body of Christ and in front of the Lord Himself: “We smile, but oh great Christ/ To thee from tortured souls arise.” The Jim Crow facial expressions, the dancing and shucking and jiving of “This is America” are modern manifestations of the masks that Dunbar describes over a century ago.

Many years later, former Black Panther Eldridge Cleaver wrote about the mask again (as did many before him) in a collection of essays called Soul on Ice (1965). In the tradition of James Baldwin, Zora Neale Hurston, Richard Wright, and so many others, Cleaver is able to poignantly explain the ways in which white supremacist ideology becomes internalized by those who have been the subjects of its abuse. In his chapter on “The Negro Celebrity” Cleaver explains that if an African American becomes successful because of his or her body—as an athlete, entertainer, etc.—then that is culturally acceptable. But if he or she begins to speak, to show intellect, to object or show real emotion, they are seen as dangerous. This very much relates to the long, cruel tradition of minstrel shows, something that Glover, as Henry points out, is obviously alluding to in his video. Both black and white performers donned black face, creating childlike, foolish, yet entertaining characters, thus reinforcing dangerous and demeaning caricatures of “Blackness.”

In Lorraine Hansberry’s 1959 Broadway play, A Raisin in the Sun, the retelling of her own family’s struggle to move in a white Chicago neighborhood, she shows the devastating impact of internalized white supremacy. Walter Lee Younger, the surrogate head of his impoverished family, initially decides to take a bribe offered to him by a white neighborhood society in exchange for an agreement that the family will not move into the neighborhood. Walter Lee has claimed that the world is the white man’s, with unjust rules based only on the making of money, and that he must play the “man’s” game in order to succeed. In his eyes, he can only be a man and have a sense of family pride if he makes lots of money in order to have nice things, what Cornel West and Nathaniel West both refer to as “the paraphernalia of suffering.” It almost seems as the gospel choir ecstatically singing, “Get your money, get your money, get your money, black man” is the backdrop for Hansberry’s play. When Walter Lee tells his family about the dirty deal, he drops on his knees and exclaims “We’ll put on a show for the man. Just what he wants to see…Maybe I’ll get down on my black knees…All right, Mr. Great White Father!”. His family is horrified as he goes through the motions of a minstrel show performance, admitting that if it promises success, he will become the caricature.

This internalization of a caricature for the sake of success is something that both hip hop artist, Lupe Fiasco, and film director, Spike Lee have critiqued in their own art. In Fiasco’s “Dumb it Down,” he makes it clear that he refuses to play dumb, to just put on a “show,”to be a body without a voice. He explains that he is peerless, like one driving a car, alone, looking through a windshield that is “minstrel.” The entire song is a scathing critique of his industry peers and the corporate world that produces them. In this sense, it is very similar to Lee’s darkly comic film Bamboozled about a stage production turned television show in which the black actors sing, dance, and wear blackface. The “dumbed down” lyrics that Fiasco is resisting and the shucking and jiving of Lee’s actors are both examples of what they have been told it takes to become successful in a culture largely dominated by white supremacist ideals. Spike Lee is known for his critique of Tyler Perry’s films and television shows, shows that he seems to think are focus on dumbed down, bodily humor rather than intelligent scriptwriting; he has even controversially referred to this as “coonery buffoonery.” Another song and video by Lupe Fiasco, “Bitch Bad,” examines misogyny in hip hop music, showing young black girls, teenagers, and women describing themselves in sexist terms. The video ends with a man and and a woman applying blackface makeup on their faces, tears rolling down their cheeks. Once again, he is arguing that playing the popular hiphop game of misogyny and “dumbed down” language is another layer of minstrelsy.

These examples and Childish Gambino’s jarring video also relate to the recent ban on NFL kneeling. In Soul on Ice, Eldridge Cleaver explains the mechanism at work: “By crushing black leaders, while inflating the images of Uncle Toms and celebrities from the apolitical worlds of sport and play, the mass media were able to able to channel and control the aspirations of the black masses…

This technique of “negro control” has been so effective that the best-known Negroes in America has always been—and still are—the entertainers and athletes.” Interestingly, we see that the dominant American culture seems at peace with successful black athletes such as Colin Kaepernick and black entertainers such as Beyonce. But what happens when the athlete becomes a political activist and the diva creates a video, such as “Formation,” that names and celebrates her blackness? The black body is united to the black mind in the collective consciousness, and this becomes a threat.

Donald Glover, along with the other artists and activists mentioned, reveals the underlying narrative of the devastating internalization of white supremacy. As he dances, smiles, wears the mask and parties, we see him destroying other black bodies. He is turning on himself because he has been told that it is the only way to succeed. And Glover, as well as his ingenious predecessors, prophetically subverts the dominant narrative to challenge us to have eyes to see and ears to hear the cries of injustice underneath the smiling faces.