Superman and... Empathy?

Hi, friends!

I am sorry for the recent lack of newsletters. It has been a very, very busy semester. But I am delighted to get back into the swing of substack things!

This semester, I have been teaching a new course called The Graphic Novel, and so many of the texts have pointed my heart and imagination in the direction of empathy. Perhaps the most surprising find in this category is Gene Luen Yang’s Superman Smashes the Klan.

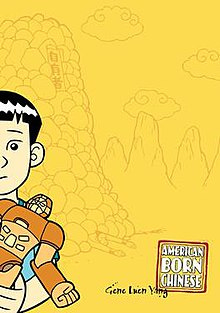

I have never been a big fan of superhero stories (either in the form of movies or comic books). But in teaching this class, I knew I needed to choose several works from this genre, even if they did not initially pique my interest. I decided to chose this particular Superman text because I loved Yang’s brilliant American Born Chinese about his experience as a young Chinese immigrant trying to assimilate in a public school.

Superman Smashes the Klan also focuses on a family of Chinese immigrants, including young protagonist Ramona Lee. The most fascinating aspect of this book is its rich history: it is based off of a 16-part radio serial called “Clan of the Fiery Cross” which aired in 1946 as part of the Adventures of Superman radio show. The story of both the original series and Yang’s graphic novel focuses on the anti-Asian attacks that occurred in California in the 1940s. In the story, the Lee family is newly relocated Chinese immigrants who are repeatedly harassed by the KKK.

Of course, Superman swoops in and ultimately saves the day–but the most meaningful parts of this comic are the conversations between Superman and young Ramona about the nature of identity and belonging. Their unlikely similarities are reflections of Yang’s own childhood insecurities, the very things that pulled him in the direction of Superman. Yang explains that, as a child, he never saw likenesses of himself in the comics that he loved. But Superman’s story did parallel his own story in multiple ways: both were “foreigners” from distant places, both had a family name that was different than their American name, both must change from one type of clothing into another in order to assimilate.

The story contains some surprisingly tender moments between preteen Ramona and Superman as they talk about the superhero’s resistance to fly. As Superman confesses to this child that he is afraid of using his “foreign” abilities in a place that does not understand him, the two bond over the identity confusion so often inherent in the immigrant/refugee experience. Superman’s vulnerability is surprisingly human–and Ramona sees and feels this: ““It’s as if you only want to be half of who you actually are.”

Although the comic deals with some obviously dark subject matter, the way it is handled is complex and empathetic. Ramona’s brother, Tommy, plays baseball with Chuck, the nephew of the local Clan leader. Yang very much humanizes Chuck, a young boy torn between the identity-forming racism of his family and an allegiance to the “goodness” that Superman, his greatest hero, both espouses and enacts.

The representations of racism in the graphic novel, both overt and covert, are very nuanced and challenging. Yang’s approach to the subject matter is, at the same time, both mature and accessible for children. It is wise, kind, beautiful, and complex. I highly recommend this book for both adults and children.

Before I sign off, I wanted to tell you about a free online opportunity to take part in a 3-day conversation about faith and art. If this interests you, check out the FIELDMOOT site and sign up for free! The conference starts tonight(Thursday, Nov. 3) and runs thought mid-day on Sunday. I know this is last minute notice–but don’t fret! All of the lectures and concerts are recorded, and if you sign up, you have access to all of them after the conference is over.

Thanks so much for reading, all!

God bless,

Mary