Welcome to The Empathetic Imagination! This newsletter was born out of my interest in the relationship between the arts and spiritual formation, particularly the cultivation of empathy (which also led to my book). In this weekly newsletter, we will look at the connections between art, theology, and the hard work of being a loving, truthful human being. If you appreciate my writing, consider buying me a cup of coffee (one time gift) or becoming a monthly subscriber!

I love conversations about movies almost as much as I love watching movies. So I was quite excited to see the New York Times list of “The 100 Best Movies of the 21st Century” come out. As part of the fun, you can scroll the list and read reviews, read which actors and directors voted for which films, and even make your own voting ballot). I am eager to share my list with you and to hear what films you have chosen!

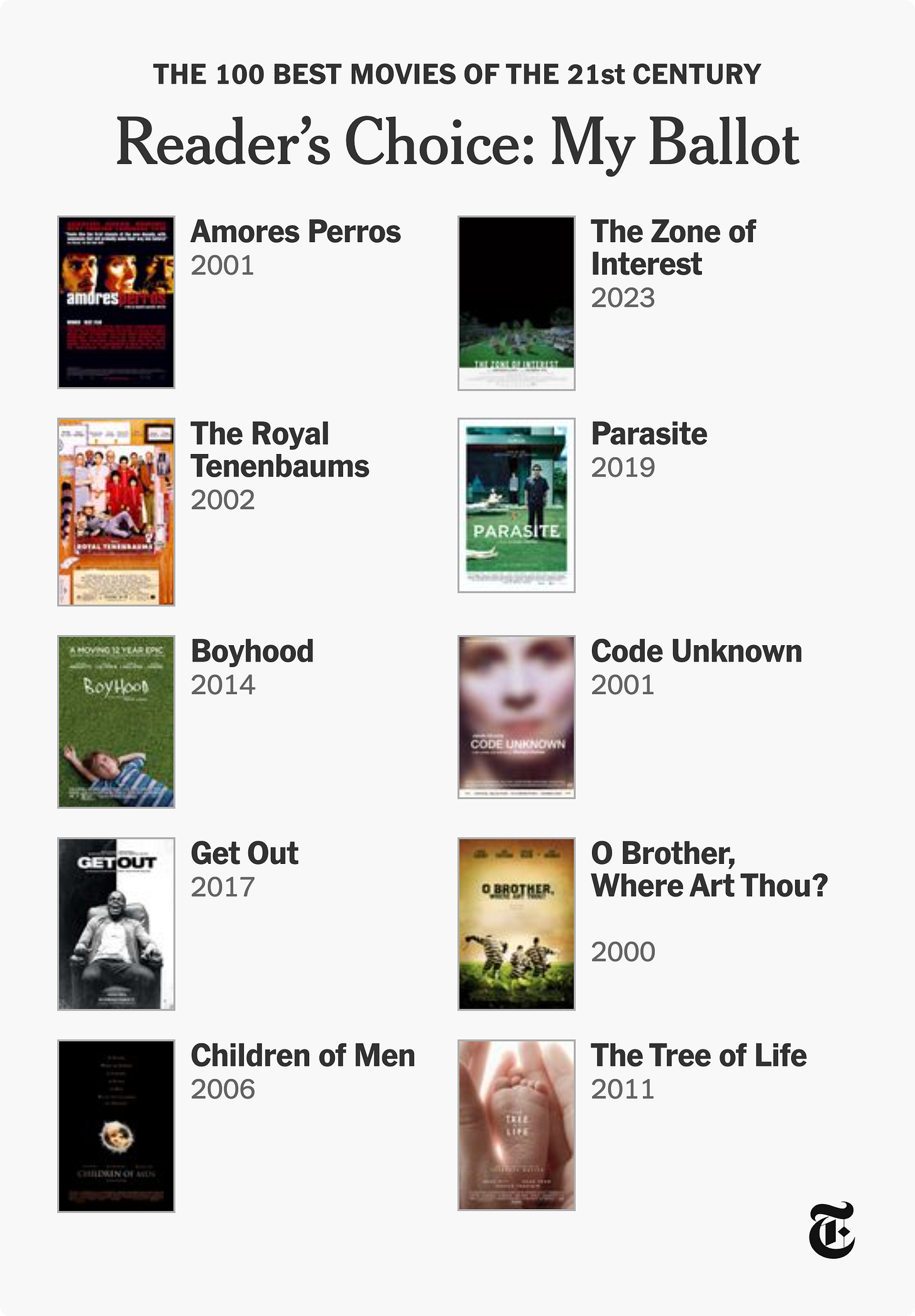

My Top 10 ballot is below, and I am still not sure I have chosen my favorite films of the last 25 years (of course, my actual list includes far more than ten).

I will not claim that these are the best films of the 21st century (although I think many of them are), but I will claim that these are all films that I find worth revisiting over and over. Like any great films, these all lead to good, rich conversations.

All of my choices are fiction feature films, as it was just too hard to also include documentaries! Below my ballot, I say a few words about each film (some include excerpts from my own previously published content). At the very bottom of the page, I provide a list of some wonderful films that I probably should have also put on my list!

HERE WE GO!

The list below is not in any particular order except for the NUMBER ONE SPOT. I cannot think of a finer film of the last 25 years than the one I have in first place…

1. The Tree of Life (2011) by Terrence Malick:

Malick’s film is both abstract and concrete as it invites us to consider the relationship between its macro-narrative—God, the creation of the world, and the moral structure of the universe—and its micro-narrative of the O’Brien family as they grapple with questions of suffering, justice, and the knowledge of God. Mr. O’Brien (Brad Pitt) follows the self-serving, purely pragmatic “way of nature” until he finally realizes that “I dishonored it all and did not notice the glory.” O’Brien learns that, in order to love his family, God, and creation, he must notice its complexity and allow himself to be ushered into a space of awe and wonder.

The Tree of Life, a highly conceptual, impressionistic coming of age film focused particularly on the internal landscape and spiritual journey of Jack O’Brien, causes its viewers to think about their own relationship with beauty and its ultimate source. Our attentiveness, or lack thereof, to the “glory”of the film tells us something about our own sojourning, about the particular kind of attentiveness, amidst both pain and beauty, that is formative in the development of our own spirituality. By forcing his viewers into a sometimes uncomfortable state of confusion, Malick often leads us into a state of wonder.

The above excerpt is from a piece I originally wrote for Relief Journal. It was also reposted by The Rabbit Room, and you can find all of it HERE.

2. The Zone of Interest (2023) by Jonathan Glazer (loosely based on a 2013 novel by Martin Amis)

This was my favorite film of 2023. It is an incredibly important film, especially in our current political context. I wrote A LOT about it HERE. Here is a short excerpt:

Glazer’s film is a Holocaust film unlike any I have ever seen. In fact, it is unlike any film I have ever seen on any topic, especially one this tragic and harrowing. In it, we follow the daily life cycles of Nazi Commandant Rudolf Höss and his wife, Hedwig. Although Höss is the architect of the many structures of death and torture contained inside the walls of Auschwitz (the ovens, the use of Zyklon D, the gas chambers), he is a well-loved and gentle father. He spends time cradling his beloved horse and reads fairytales to his daughter.

As I watched the film’s beautiful images full of love and light, I kept thinking of the word “wholesome.” This reminds me of James Baldwin’s brilliant letter to his nephew in which he refers to those upholding white supremacy as “innocents.” These innocents have –in both past and present–oppressed and dehumanized his people. They are “innocent” as they believe so strongly in the normality of the privileged, “wholesome,” lives they provide for their families. And in order to do this, they must willfully ignore and/or normalize the brutality that must occur in order for this normalized, exclusive, privilege to be maintained.

3. Get Out (2017) by Jordan Peele:

I have never been a big fan of horror films, but Get Out is more focused on social satire than gore. It makes total sense that a film about America’s most malevolent and internalized set of conspiracy theories–white supremacy–would be a horror film, just like it makes sense that Toni Morrison’s memorial to slavery, Beloved, is a ghost story. Jordan Peele is known for comedy, and this film is at times hilarious–but it is also sad, true, and insightful.

When Chris finally has the nerve to meet his white girlfriend’s parents, he enters a world of white picket fences, garden parties, and subterranean nightmares. Peele’s critique of white “I have a Black friend” liberalism is both chilling and poignant.

4. Children of Men (2006) by Alfonso Cuarón:

The familiarity of Children of Men is harrowing, but this makes its glimmer of hope even more profound. This film is a parable for our divisive American landscape. Although we do not walk through burnt out, body-filled streets, we encounter chaos and dissonance almost every time we turn on the news or go online. Our social and political selves are fractured and fragmented, and it can be hard to be hopeful in the midst of this backdrop. Even if the horrors we see are not our individual experiences, we are aware of the refugee children in cages, the people of color being “policed” in inhumane ways and the fear of “the other” infiltrating our collective cultural mindset.

Zizek explains the background of Children of Men must stay as the background to impact the viewer: “If you look at the thing too directly, the oppressive social dimension, you don’t see it,“ he says. Perhaps we can’t see injustice and oppression in the foreground because they become normalized. When we see shocking images in our Facebook feed, how quickly do we become used to it?

This is part of an article I wrote for Relevant Magazine. You can read it all HERE.

5. The Royal Tenenbaums (2001) by Wes Anderson

Of course, I had to include a Wes Anderson film as his brand of sincere, nostalgic quirk is completely unique its use of both irony and sincerity. I would include Anderson’s films in the new-ish category of metamodern art. If you would like to learn about this off-kilter genre, I suggest checking out my post about another Anderson film. In this film, Anderson sets a precedent for his future dysfunctional family films, focusing on the wounded children of a neglectful, narcissistic parent. Although this story is deeply sad, it is so stylish, charming, and so storybook-sentimental that it is hard not to smile. And the soundtrack to this film is perhaps my favorite soundtrack to any film ever (well, any film that uses popular music rather than scores).

6. Code Unknown (2000) by Michael Haneke:

This is definitely one of the more conceptual, “difficult” films on my list. I really love it, but it took me multiple viewings to get there. Interestingly, I could not find a trailer for the film with English subtitles, and this is very fitting. It is a film about the gaps in communication, both in art and life.

I both recorded and wrote something about it in THIS SUBSTACK POST. Here is an excerpt:

As a filmmaker, Haneke’s prime means of communication is “mediated reality,” and Code Unknown, in particular, interrogates this. In an interview about Code Unknown, Haneke explains that “A film is not reality. It is a model of reality, if you like. Reality is too complex to capture.” He continues by making the point that it is even more difficult to make a documentary than a fiction film, in this regard, because a documentary shows only a tiny part of real “reality” yet claims to represent reality itself.

Along these lines, perhaps nonfiction is less true than fiction because fiction does not claim to be “real.” The oft quoted Picasso line gets close–but perhaps not close enough–to the truth of the matter here: “Art is a lie that makes us realize truth, at least the truth that is given us to understand.” Yes, art is a “lie” when it pretends to hold up a mirror reflecting reality. After the modernist “crisis of representation” following World War I, many artists were challenging the notion that linear narratives, “realistic” portraits, and the like were honest depictions of “reality.” In fact, these conventional art forms were the most dishonest, claiming mimesis (direct imitation) when there is no way to recreate any sort of objective reality in art.

7. Amores Perros (2000) by Alejandro González Iñárritu

This is a brutal film about ongoing class warfare in Mexico city, symbolically represented by the cruelty of illegal dog fighting. I saw it in a cinema in the UK with a housemate from Mexico, and I learned so much about the Mexican class system from her as we watched and discussed the film. There are three different storylines about three different groups of people, each from a different social class. The use of multiple narratives is one of my favorite film techniques and one that Iñárritu truly masters (I also like his films 21 Grams and Babel that use the same technique). I have not seen this one in a while and really need to revisit it although it promises to be a harrowing experience.

8. Boyhood (2014) by Richard Linklater:

In the second half of Richard Linklater’s beautiful film Boyhood, the detached, seemingly sullen protagonist Mason (Ellar Coltrane) meets a pretty girl named Sheena at a very typical high school party. Teenage Mason is not the talkative, openly inquisitive boy of his younger years, but when he speaks with Sheena, something clicks. He enjoys talking to her, and he admits it openly. As he realizes this shift in himself, he explains that he never tries to verbalize his thoughts or feelings because it usually “does not sound right.” Besides, he thinks, “words are stupid.”

This scene might sound like typical juvenilia. And on one level, it is. Linklater’s film—which many claim is plotless—shows us the progression of a boy’s life from age six to eighteen. Much of the film’s brilliance comes from its ordinariness; there are no shocking narrative twists, and Mason’s life is as real as that of your next door neighbor’s world-weary, often silent son.

Linklater has followed these actors for twelve years, filming a ten to fifteen minute short film each year in order finally to piece them together to create the plot of Mason’s life. It is deeply important because it is so truthful. The film’s plot is life itself, the everyday miracle of growing up—tracing the milestones, joys, and challenges of childhood, adolescence, and the awkward transition into adulthood.

You can read the rest of my review–focusing specifically on the way the film examines parental “attachment” (or the lack thereof)–at Christ and Pop Culture.

9. Parasite (2019) by Bong Joon Ho

Like (but very unlike) Amores Perros, this film interrogates the artificial cruelties of a corrosive class structure, this time in Korea. It is less violent and more sparse, but just as emotionally devastating. The contrasting realities of the film’s low-income family and their upper crust employers come to a startling crash at the end. Themes of concealment, identity confusion, and reality vs. fantasy emphasize the cruelty of the false class binary.

Another film with a truly fantastic soundtrack! The Coen Brothers have a brilliant way of capturing regional dialects, mannerisms, and customs. As a Southerner who loves my cultural mythology, I truly enjoyed the directors’ references to the Robert Johnson myth, Flannery O’Connor’s “Good Country People,” and the history of George “Baby Face” Nelson. And the brilliance of telling this deeply Southern story within the framework of Homer’s Odyssey is irresistible. I have shown it in multiple classes and also spoken about how we see a merging of ancient and postmodern modes of storytelling (Ulysses is a nihilist and opportunist whereas his companions are drawn in by Judeo-Christian ideas). This is perhaps the most “fun” movie on my list. Endlessly rewatchable!

Here is my short list of films that I could not include (and I am sure I have forgotten some): Eternal Sunshine of the Spotless Mind, Almost Famous, Sound of Metal, Oppenheimer, Lost in Translation, Nomadland, Once Upon a Time in Hollywood, The Worst Person in the World, and No Country for Old Men

And here is a very short list of three of my favorite documentaries from the last 25 years:

13th by Ava Ava DuVernay

An INCREDIBLY important documentary.

You can watch the entire film below:

The Filth and the Fury by Julien Temple

Admittedly, not for everyone. But if you like British history and/ or music history (punk rock), then I highly recommend it.

I am Not Your Negro by Raoul Peck

James Baldwin is one of the most important writers and thinkers of the twentieth century, and this film does his genius justice.

Thanks for reading, all! Please share some of your favorites from the past 25 years in the comments! Until next week…

We have a lot of overlap on our lists (particularly #1)! I could see Zone of Interest on mine in about five years, after it's sat with me for a little longer.

Love seeing *your* list Mary! Made reading the NYT list all that more interesting!