Dear readers,

It has been a very busy few weeks for me, including a wonderful birthday week in Washington DC with dear friends from college! One of he highlights was finally visiting the Smithsonian’s National Museum of African American History and Culture, especially the visual art section. During my time at the museum, I realized even more that my academic work is experiencing a shift reflecting the profound influence of learning from Black students, friends, and cultural/ religious leaders. More than ever, I want to learn about African American history, literature, and culture. Of course, this is not just an academic pursuit but a personal and spiritual one. The more I learn, the more I listen, and the more I feel called to speak, to write, to learn even more. I am deeply thankful for the prophetic witness of the Black church throughout American history; it helps me to believe in the merciful God who liberates, nurtures, protects, and gives life.

Because of my limited time this week, I want to share something with you from a current project I am working on, my first academic publication on African American literature. Although I have written for pop publications on Black film and fiction, I have not yet published an academic article or chapter on African American literature. My first piece is from the forthcoming first academic collection on the writing of Jesmyn Ward, a young Black Mississippi author. Ward has won the National Book award twice for two novels, Sing, Unburied, Sing (2017) and Salvage the Bones (2011). I decided to write on Ward’s memoir, Men We Reaped (2013), the story of unrelenting poverty, pain, and grief that punctuated Ward’s early years in DeLisle, Pass Christian, and Gulfport Mississippi. The title of my chapter is “A Prophetic Haunting: Bearing Witness Against Black Nihilism in Jesmyn Ward’s Men We Reaped,” and you can find a chapter overview(abstract) below.

The following photo is taken from an NPR interview with Ward. In it, she sits in front of her grandmother’s house in Pass Christian, Mississippi.

Near the beginning of her memoir, Men We Reaped, Jesmyn Ward describes a reckless party at a local club referred to as “Delusions,” one of the many spaces in the novel where Ward and her friends self-medicate. Suffocated by grief while fearing the ghosts of the dead, they gravitate closer to the “Nothing,” an empty, hungry spirit of death that is always “stalking” them. While at the club, the drunken friends take a photo in front of a fantasy backdrop, “a city-coast skyline that was completely alien” to life in the fields and bayous of their native Mississippi. Around the photograph is a border with the words, “God’s Gift” cradling the image of a shiny, momentarily happy, ever despairing group of young friends. The ironic notion that their lives are a gift from a seemingly absent God is perhaps, to Ward, the greatest delusion.

Although growing up in the Bible belt and working as a teenage counselor at a Christian camp, Ward’s youthful faith soon transforms into an acute sense of abandonment. Once she bears witness to the fragility of Black existence, losing five young men within a span of four grief-soaked years, she cannot believe in a loving God. Ward explains that, as a young teenager, “I found irresistible the idea of a God who loved me unfailingly” but “In the end, I realized sometimes, some people were forsaken.” Ward’s story is not only hers; it is about an “entire community” that “suffered from a lack of trust” because of the ways in which they were denied access to education, safety, justice. And because of this, we “trusted nothing” and suffered from a deep sense of hopelessness: “Some of us turned sour from the pressure, let it erode our sense of self until we hated what we say, without and within.

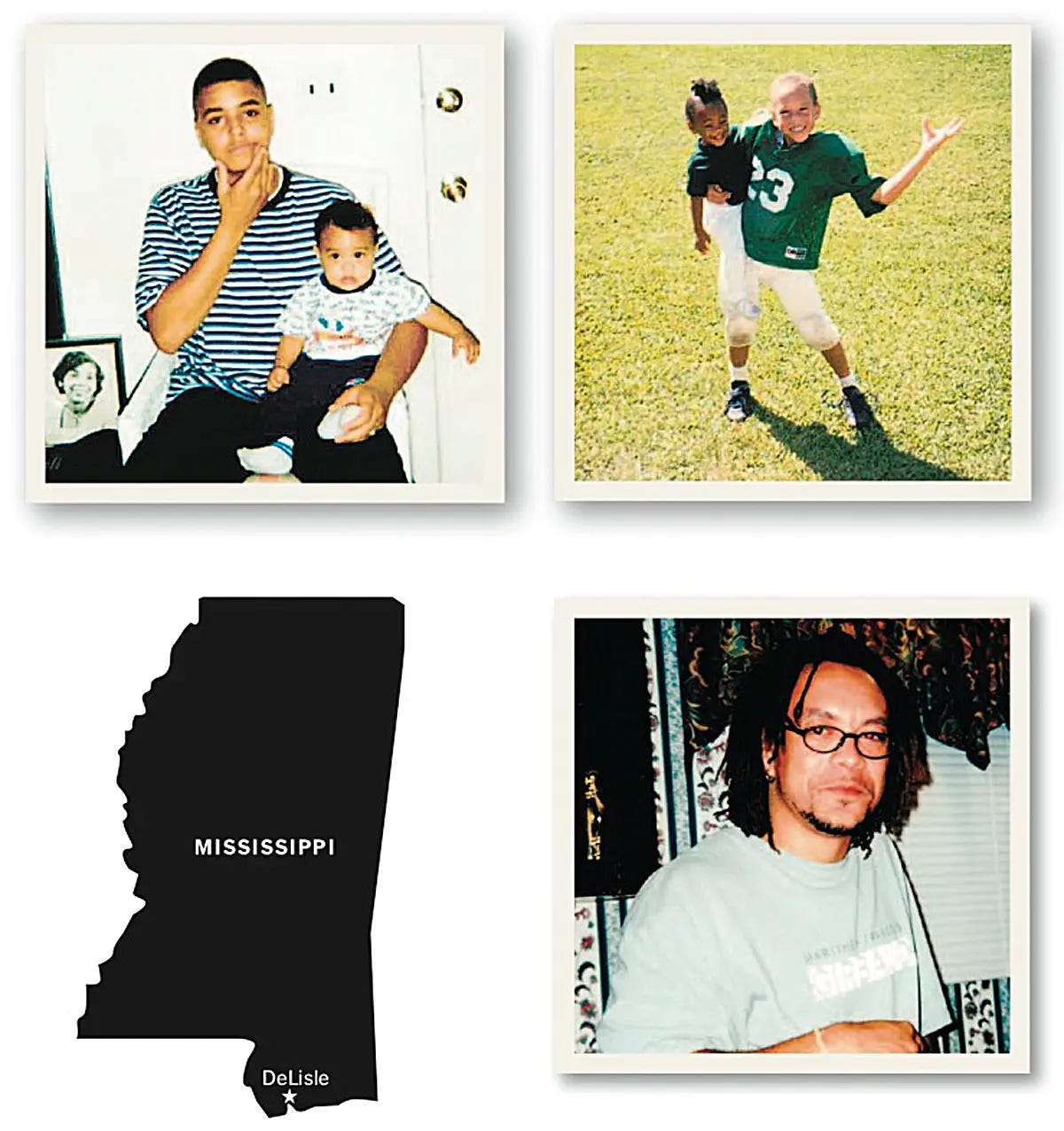

The photo below was taken from the New York Times’ review of Men We Reaped: “In memoriam: Jesmyn Ward's brother (top left) and two friends were dead by their early 30s.”

In Race Matters, Cornel West describes a type of hopelessness that is a “nihilistic threat” to the very existence of Black America. He calls this nihilism “a disease of the soul” rooted in a “profound sense of psychological depression, personal worthlessness, and social despair so widespread in Black America.” When Ward’s friend Ronald unexpectedly commits suicide, she understands his motives. They shared the same sense of despair, a need to “silence the self” and, in turn, “silence the world” through an act of self-extinction. They are both pawns in a game beyond their control, because, as Hansberry’s Walter Lee Younger explains, “I didn’t make this world! It was give to me this way!”. Ward’s sense of powerlessness in a world that is unsafe for the Black men that she loves is intensified by her sense of divine abandonment.

Although chased both by the mysterious, ravenous “wolf” of death and the temptation of nihilism (“I am nothing”), Ward perseveres and survives. She explains that in writing her first novel, she pretends that she still believes in a “benevolent”, just God—but in telling these stories of senseless loss, she realizes that, as an author, she needs to be, “an Old Testament God.” The more she is haunted by the ghosts of the dead, the more she knows that their stories must be told in order for her to live. Storytelling is an act of resistance against the silence that will consume her into its nothingness. In The Future of Race, West explains how this “guttural moan” of testifying to Black grief is a “fragile existential arsenal—rooted in silent tears and weary lament” that “supports Black endurance against madness and suicide.” Although Ward’s story is written in the shadow of a seemingly absent God, her storytelling serves a prophetic function, exposing injustice, bearing witness to pain, and pushing against the despair that leads to death.

In an unbelievably tragic, ironic turn, Ward’s young husband, Brandon Miller, died right before the pandemic. She wrote about his death and her grief in an article for Vanity Fair.

I cannot recommend Ward’s writing enough, especially Men We Reaped.

As always, thanks for reading.

Mary

Thank you, Mary. I really appreciated reading this and will seek out Jesmyn Ward’s memoir. Ward’s Vanity Fair article is heartbreaking and powerful.