Banning Books, Decreasing Empathy

Dear friends,

Before I dive into the topic of this newsletter, I want to invite you to join the launch team for my new book, Imagining Our Neighbors as Ourselves: How Art Shapes Empathy. If you sign up, you will receive a free pdf of the book about a month before it comes out; you will also have the opportunity to order a hard copy for 30% off. Once you have read the book, I ask that you leave a review somewhere online, as well as share book info on social media, with your church, etc. If this sounds good to you, just enter your email address HERE.

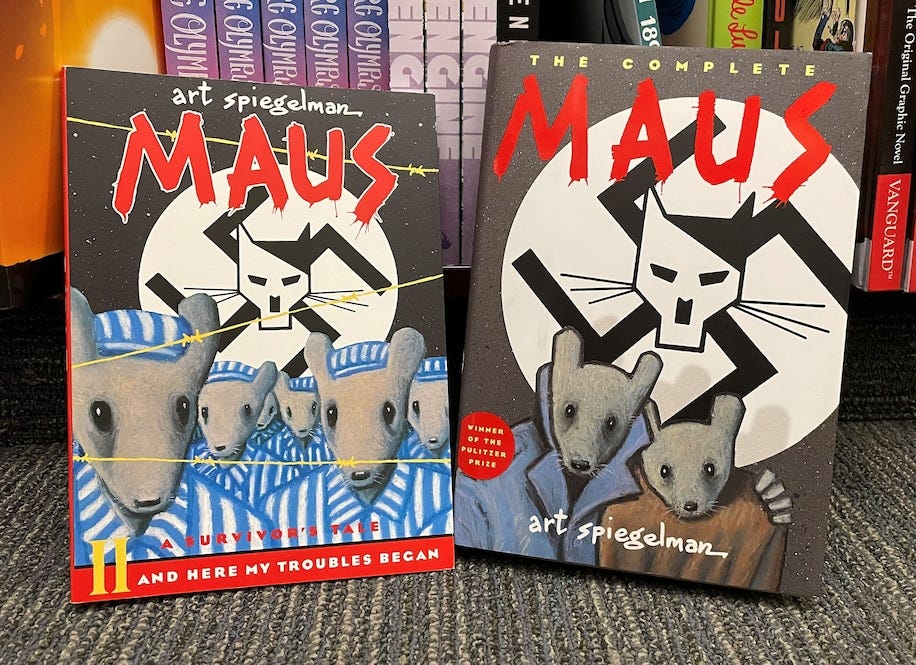

I had planned to talk about a completely different subject today (stay tuned for my next newsletter on African American spirituals!) but my focus shifted when Maus, a graphic novel (comic book) about the Holocaust that I teach every spring, was banned from a neighboring county’s public schools. Although this frustrated me, the topic became even more urgent after hearing the name “Isabella ‘Izzy’ Tichenor” for the first time in a church prayer Sunday morning. Izzy was a Black, autistic ten-year-old who recently committed suicide after being bullied because of her race and disability. This tragedy occurred in Utah, in the same school district that has been investigated by the Department of Justice for failing to respond to blatant acts of classroom racism. Administrators in the Davis School District denied and downplayed the bullying that Izzy endured, just as they did when a Black child was dragged by a school bus because the driver intentionally shut the door on his jacket.

You might be wondering what these very sad real-life stories have to do with banning books like Maus. A lot. There is an intrinsic connection between the removal of books about the painful reality of American history and a decrease in empathy for those who are marginalized. In some cases, the same administrators who are ignoring the immediate, destructive impact of racism on the lives of Black and Brown children also want to remove any books about history that they think *might* make white children feel uncomfortable. So the possible minor discomfort of white children is privileged above the definite instances of racial bullying that Black and Brown children must endure.

We see this clearly in the attempts to ban Ruby Bridge’s autobiographical children’s story (pictured above) documenting her experience as the first Black child (just 6 years old) attending a previously segregated school in Louisiana. Moms for Liberty, the same Tennessee-based group that wants to ban Ruby Bridges’ story from public schools also wants to ban the story of Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr., claiming that it is “anti-American.” Robin Steeman, head of Moms for Liberty, claims that Ruby Bridges Goes to School should be removed because, in the book, a"large crowd of angry white people who didn't want Black children in a white school" too harshly delineated between Black and white people, and that the book didn't offer ‘redemption’ at its end.” She also wanted to remove words such as "injustice," "unequal," "inequality," "protest," "marching" and "segregation" from grammar lessons.

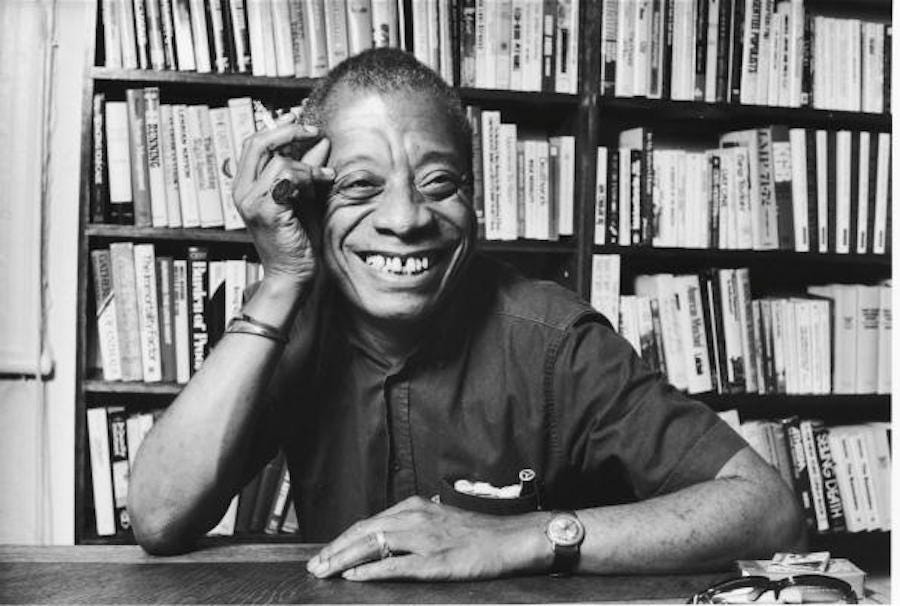

The desire to always serve up happy endings–rather than speaking the truth in love–is greatly damaging to all children. As MLK, Frederick Douglass, and James Baldwin all point out, racism is just as damaging to the oppressor as it is to the oppressed. Like the very love of power that spawns it, racism is soul corrupting. I am not saying that white children are inherently “oppressors.” It’s just the opposite, in fact. Racism is a result of socialization, and we must intentionally work against that sort of socialization–the type that would rather teach whitewashed fairy tales about history that expose all children to the true stories of demonic abuse and oppression, something that we want them to see as wrong, devastating, and inhumane. But how will they know this if we don’t teach them?

In a famous letter to his nephew, the often prophetic James Baldwin says this about his young nephew’s future relationship with white people:

“The really terrible thing, old buddy, is that you must accept them, and I mean that very seriously. You must accept them and accept them with love, for these innocent people have no other hope. They are in effect still trapped in a history which they do not understand and until they understand it, they cannot be released from it. They have had to believe for many years, and for innumerable reasons, that black men are inferior to white men.”

Baldwin sees the act of telling the truth of history as an act of love. And he tells his nephew that, as hard as it is, he must love white people in this way in order to give them the “hope” to see reality more clearly. Although Baldwin and his nephew were in Jim Crow chains, the “innocent” white people who benefited off of their oppression (sometimes without even knowing it) were in mental and spiritual chains. He then explains that speaking the truth and challenging white superiority is very frightening for white Americans because, “the danger in the minds and hearts of most white Americans is the loss of their identity.”

Yet in 2022, many school districts are seeking to ban books that tell the truth about both the ugliness and beauty of history, often using the catchall bogeyman phrase “CRT” (incorrectly) when describing these books. Instead, they choose to peddle the spiritually crippling fairytale of American exceptionalism. In a recent article, Jemar Tisby (read his books if you have not!), points out how illogical the notion that banning books about race will lead to greater moral character is: “How absurd the notion that people in the United States should learn less about race and not more. As if the problem is that we know too much about the subject and not too little.”

As both Tisby and Esau McCauley note (in The Color of Compromise and Reading While Black), as Christians especially, we must bear witness to the truth of past and present sins before any kind of actual reconciliation can occur. And honest, nuanced, historically accurate classroom education can be an invaluable step toward this. I am no longer surprised when I teach the Narrative of the Life of Frederick Douglass to students and find out that they had no idea that slave families were separated from another. I am no longer shocked when I find out that they do not know the names Emmitt Till and Ruby Bridges. I am no longer shocked when I find out that have only read snippets of MLK’s “I Have a Dream Speech,” often taken out of context. I am not shocked–but I am sad. And so are they. As they read, their hearts soften, their imagination expands, their capacity for empathy grows. And they are often angry that they were never taught these things.

In a few months, I will once again be teaching Art Spiegelman’s Maus. Although Maus is not really a book for eighth graders (mainly because of a graphic depiction of suicide), it tells a truth that should not be banned. The irony of banning a book about the evils of Nazi Germany is stunning. Just as much as Maus is a book about the Holocaust, it is also a book about the impact of intergenerational trauma. Spiegelman writes himself into the story; in fact, his is just as much a protagonist as is his father, Art, an Auschwitz survivor. In the graphic novel, we see images of Art drawing, images of Art listening to his father’s story, images of Art’s struggle with to knowhow to love and care for an emotionally absent, deeply traumatized, even abusive father. Maus reiterates the importance of passing down the true story, the whole story, if healing is to ever occur.

“The way to battle the ban is to lean in to love. Lean in to that timeless, irrepressible love of books. Lean in to the feeling of being transported by an engrossing story. Lean in to the satisfaction of feeding our famished brains with new knowledge. Lean in to our notorious affair with the written word.”—Jemar Tisby

Thanks so much for reading. See you next time!

Mary

p.s. Don’t forget to SIGNUP for the book launch team and get a free advance copy (pdf) of my book!