In My Bright Abyss: Meditation of a Modern Believer, poet Christian Wiman writes this:

"In truth, experience means nothing if it does not mean beyond itself."

An isolated moment can bring intense joy–but what is its “meaning” if not connected to a larger chain of events, a set of memories, a story? Human beings long for connections that ultimately become narratives. “It’s not healthy to live life as a succession of isolated little cool moments. Either our lives become stories, or there's just no way to get through them” writes Douglas Coupland in his novel, Generation X: Tales for an Accelerated Culture. We long for narratives that move toward a denouement, the “working out” and tying together of all the loose story strands. When processing this final “truth” of the story, we use this revelatory (“apocalyptic”) information to go back and reread all events leading up to it. Then we hopefully find closure and meaning.

But in the present-day setting of Christopher Nolan’s movie-puzzle Memento (2000), protagonist Leonard Shelby experiences life in isolated moments that are erased within minutes of being experienced. There are no connections, one to the other, with the new occurrences in his life. Leonard suffers from anterograde amnesia, and–unlike someone with amnesia–Leonard does not completely forget all of his past, only the isolated moments that occur after the traumatic “incident”–that led to his brain damage.

We will meet this Saturday, June 1, at 2 pm ET to discuss the film on Zoom. I will send a reminder and Zoom link on that date.

In an interview about the film, director Christopher Nolan explains the complex difference of Leonard’s “condition:”

“In an amnesia movie, there are no rules. Anything can be true….It’s too easy. This is a much more controlled space that is blank in the guy’s personality. This is the space between the person you are now and the person you once were. All the objective information by which you define yourself (name, where you live, childhood, etc.) that’s all accessible. It’s the difficulty of reconciling that with his present self.”

The film’s structure invites us to experience the present moment just as Leonard does. Nolan explains that “I wanted to deny the audience the same information that the protagonist is denied.” In doing this, the man character is “cut loose in time,” and so are we. Nolan creates this effect ingeniously by telling the story in two different narrative threads: one is in color, one is in black and white. While the color sequences tell the story subjectively and backwards, the black and white sequences are more “objective” and tell the story in a straightforward, linear fashion. But things are really not that easy for the viewer. The film’s subjective threads, at times, blur with the film’s objective threads. And the ending…WHEW.

Nolan’s interest lies in creating “tension between our subjective view of the world–the subjective way in which we have to experience life” and “our faith in an objective reality beyond that.” The “facts” that Leonard sees as objective are the labels that he has learned to navigate life. For instance, in one sequence, he explains that when he knocks on an object, he knows it will make a sound. But how does he know this? He has learned via observation and repetition retained by memory. He now has faith in his belief in this particular cause and effect. Interestingly, Nolan is pointing out the relationship between epistemology (the way in which we know things, gain knowledge) and faith. Memory is a key element in knowing, and both memory and knowledge are connected by faith in past and present experience.

Leonard also has an emotional past memory, including his deep love for his wife. He does not just know “facts” about her (where she is from, her name, her height) but internal emotional “facts” about the way he feels about her. Can he trust this as much as the external “facts” about the way he reads the everyday nature of reality?

Nolan explains that “Most movies present a quite comfortable universe where we are given an objective truth that we don’t get in everyday life.” He claims that this is “one of the reasons we go to the movies.” We want to believe that we actually know what is real, that there is an objective reality that will accompany us to the “end” of our stories.

Philosopher Thomas Wartenberg elaborates upon the way films are technically created with the aim to provide us with an illusion of comfort:

“Classical Hollywood films were shot and edited with a view to making the viewer comfortable as he or she watched the film. Since editing together two shots breaks the continuity of the scene portrayed in a single shot, a system was developed that allowed audience members to easily interpret how the later shot was related to the earlier one. A series of conventions – eye-line matches, establishing shots, the 180 degree rule, etc. – was developed that allowed viewers’ experience of a film to be uninterrupted by the intrusion of editing and other camera techniques. As a result, this style of filmmaking was claimed to make the act of filming transparent, meaning that the audience would watch a film so constructed with no conscious awareness of how its experience was being shaped by the filmmakers.”

Nonetheless, the desire to make audiences more aware of films as constructed burns undiminished in the hearts of the more adventurous filmmakers. Christopher Nolan’s film, Memento, breaks interesting ground in this regard.”

And in Memento, Nolan is constantly calling our attention to the constructed nature of a story–both the internal, subjective parts of the story and the external, seemingly objective parts of the story. Which do we trust the most and why?

At one point in the film, Leonard’s voiceover (his internal voice) says, “I have to believe in a world outside of my own mind. I have to believe that my actions still have meaning…I have to believe that when my eyes are closed, the world’s still there.” Like all of us, Leonard wants to believe that there is an objective reality that he can trust. But without the aid of present-day memory, how can he know if it exists? And if it is dependent on memory, is it truly objective?

In a chapter on Jacques Derrida in James K.A. Smith’s Whose Afraid of Postmodernism: Taking Derrida, Lyotard, and Foucault to Church, Smith notes that Leonard uses all kinds of written texts–written notes, polaroids with writing on them, tattoos on his body–in order to “provide a framework for him to understand his world” (32). In this sense, “Leonard’s entire relationship to the world is mediated by texts”(33). Nolan is calling our attention to the question of hermeneutics–all of our understanding of reality is mediated by something that must be decoded. In this very Derridean sense, all of the world is a text. Yet the question is still there: “How does Leonard know his texts really represent the world outside of his mind?” (33).

Our memories are also texts to be interpreted and reinterpreted. In the aforementioned interview, Nolan explains that the film also examines “the complex relationship between imagination and memory.” Leonard knows that he is no longer able to create any memories, so the texts he writes act as his only memory of events since the incident. But how do we know these texts are correctly interpreted, especially as they have no context and exist independently.

"In truth, experience means nothing if it does not mean beyond itself." –Christian Wiman

Nolan admits that Leonard is the “most unreliable of unreliable narrators” as he is able to manipulate the meanings and interpretations of his memories as he records them on paper. In considering the film’s questions about the relationship between memory and the imagination, I could not stop thinking about William Wordsworth’s beautiful homage to the importance of memory (and its intrinsic connection to the imagination), Lines Composed a Few Miles Above Tintern Abbey.

In some favorite lines, he writes of:

“All the mighty world

Of eye, and ear,—both what they half create,

And what perceive.”

According to Wordsworth–who was very influenced by the philosophy of Immanuel Kant– all of our perceptions are half created by our imagination. He elaborates on the ways in which this particularly impacts our memories, the ways that we “romanticize,” alter, and misremember the past.

SPOILERS BELOW:

In Memento, we finally understand that Leonard has intentionally misremembered the past in order to achieve his goals of revenge and assuage his own sense of guilt. Although he has a “condition” that lends itself to this practice, the film seems to ask us to examine ourselves and ask how often–and in what ways–do we do the same things?

Memento is based off a short story idea by the director’s brother, Jonathan Nolan. On a road trip across the U.S. Jonathan shared his story idea with Christopher. Jonathan’s idea became a story published in Esquire Magazine, “Memento Mori,” that came out after the film Memento came out. As we consider the film’s comments on the desire for a narrative, it is interesting to consider these lines from the story:

“Everybody is waiting for the end to come, but what if it already passed us by? What if the final joke of Judgment Day was that it had already come and gone and we were none the wiser? Apocalypse arrives quietly; the chosen are herded off to heaven, and the rest of us, the ones who failed the test, just keep on going, oblivious. Dead already, wandering around long after the gods have stopped keeping score, still optimistic about the future.”

In the “creation–fall-redemption” structure of most traditional narratives, the reader longs for an apocalyptic moment in which all things are revealed. In a world without any overarching narrative, the isolated, disconnected moments of life add up only to death without any sense of fulfillment.

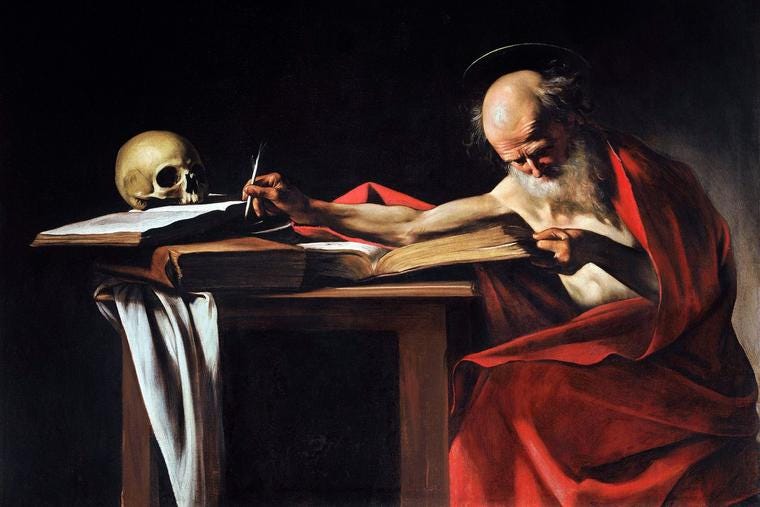

Yet a “Memento Mori” was historically a feature of the devout Christian life. This memento of the oncoming reality of death is not ultimately fatalistic but a sobering reminder that life is larger than this perceived, earthly reality. It is a reminder to believers to live humbly, to be prepared, to focus on the things that have eternal meaning.

“Keep death before one’s eyes daily.” —Rule of St. Benedict

In Don DeLillo’s brilliant satirical novel White Noise (one of my favorites!), one of the characters claims that “All plots move deathward. This is the nature of plots.” And in the opening scene of Nolan’s Memento, we see a death. The entire plot of the film moves backward towards an explanation of this death.

The written mementos of life and memories that Leonard Shelby accumulates are reminders of a plot–but is this plot moving toward a true revelation and resolution? Or is this plot moving only toward death? Are Leonard’s mementos also “memento mori”? In order for them to be, there must be a larger plot, one that moves deathward, but also beyond death to some ultimate resolution. Or are these texts just fragments–easily manipulated, isolated moments–a puzzle that can never be solved in any satisfying sense?

As this email is so full of questions already, I am not going to conclude with a question section. But here is just one question for you to ponder as you contemplate this film:

What is the significance of Sammy Jankis’ story? And how does it help us to piece the puzzle together? Or does it?

The movie doesn't ever show a newspaper story or present any kind of factual account of anybody Leonard had been married to or how any of the people in his past had died or whether or not he had been a suspect in anything like that. There isn't any information as to whether or not the person he remembers when the narration talks about what happened with a wife was a person he had been married to. Memento is a weird study in how the mind might make deductions from sketched out details when in reality the information given isn't complete or verified enough to establish what was going on. Comparative Literary types are more likely to make deductions from suggestions when the factual details aren't present in a text, is what some people think? The are those flash cards in the movie. I read that therapists can actually make tax deductions for flash cards. What awful about Memento is discussing details about the story makes it seem like you knew about something that had happened, when you might not know anything like that really at all.