Dear friends,

Thank you for reading and engaging with my last newsletter about the vital importance of art, created by both Christians and non-Christians. Today I am excited to include a bit more from artist, arts organizer, and podcaster Stephen Roach and tell you a bit about the life-enriching experience that is The Breath and the Clay (coming up March 21-22). This newsletter is not an advertisement. It is a reflection, a testimony, and another discussion of the ways to think about faith and art.

These are troubling, chaotic, divisive, exhausting times. This is an understatement.

The arts are crucial as a means of prophetic resistance and witness to True truth. What a life-giving gift it is to create and enter community around a shared love of the arts. This is even more nourishing when the shared loved for the arts is based upon the life-defining shared love of the Creator of the arts and the artists, the one who has made us in His image and implanted a desire in us to search for meaning, to be creative, to love and long for community.

During these troubling times, an arts gathering like The Breath and the Clay feels like a nourishing inhale, an injection of oxygen to the wounded, human, struggling Body of Christ.

Stephen Roach, creator of The Breath and the Clay, did not grow up in a Christian community, so this was not his framework from early on. But he told me that when he became a Christian, he had no trouble reconciling his artistic practice with his love of the Lord:

“I always knew that art was inherently spiritual, so when I became a follower of Jesus it just made all the more sense to me that my faith was going to enhance my art and that my art would enhance my faith.”

But as Roach grew into the church, he noticed some perceived uneasiness within the church walls over the subversive freedom of artists. He saw that “in Christian community, we tend to want all absolutes, certainty–unwavering truth and no room for discussion.”

In hearing Stephen’s comment, I am reminded of a temptation for Christians to lean more towards reason-based Cartesian certainty that gives us a feeling of control. But when we need to “reason” all things out to fit into our systems, it is easy to fall into what Roach calls “the idol of certainty.” Where are mystery and wonder if everything fits into our neat, tidy, rational boxes?

How do we worship someone that we think we can “figure out” using our own reason?

In this sense, the arts–their weirdness, vitality, and wildness–can help us practice making space for wonder, mystery, and worship. The arts help to make us vulnerable and vulnerability–a recognition of our weakness, our sing, and our need for redemption– is the space where we to encounter God.

“Knowing God without knowing our own wretchedness makes for pride.

Knowing our own wretchedness without knowing God makes for despair.

Knowing Jesus Christ strikes the balance because he shows us both God and our own wretchedness.”

― Blaise Pascal, Pensées

Roach does not deny the certain truth of the gospel–the absolutes of the faith that are both foundational and mysterious. But he speaks of these truths as “pillars” rather than “walls.” In this sense, the profound truths of the gospel enable us to connect and understand the pain, beauty, and mystery of other human beings rather than blocking them out if they don’t fit all of our equations. This also places us in the humble state of realizing that we know very little about God, about other human beings, even about ourselves. The art of life is an exploration of these mysteries.

This is a reminder that we all should aspire to have the faith of a child. Of course, children are eager, question-filled artists. As C.S. Lewis illustrates in The Great Divorce, children ask questions addressed to those that they believe have answers. This childlike faith is not cynical or self-righteous, it is full of wonder, delight, sometimes confusion, always trust. Could witnessing the attentive faith of the artist during artistic process help us to become more childlike, more trusting? And as we feel held by Truth, aren’t we more likely to we create, question, dance, and sing?

When talking about our tendencies toward comfortable certainty, Roach asks “When we talk about vastness of God and creative world, how can we approach this with such a tight fist and not end up creating an idol of sorts?”

These are the sorts of topics that are explored at The Breath and the Clay. Last year was my first time to attend, and it completely exploded the tiny box all of my meagre expectations. This gathering was gospel-centered but never, ever cookie cutter. There was such a presence of experimental art, the kind of art that sometimes scares Christians. But this art was created with such a spirit of joy and wonder (and absence of cynicism) that it was infectious.

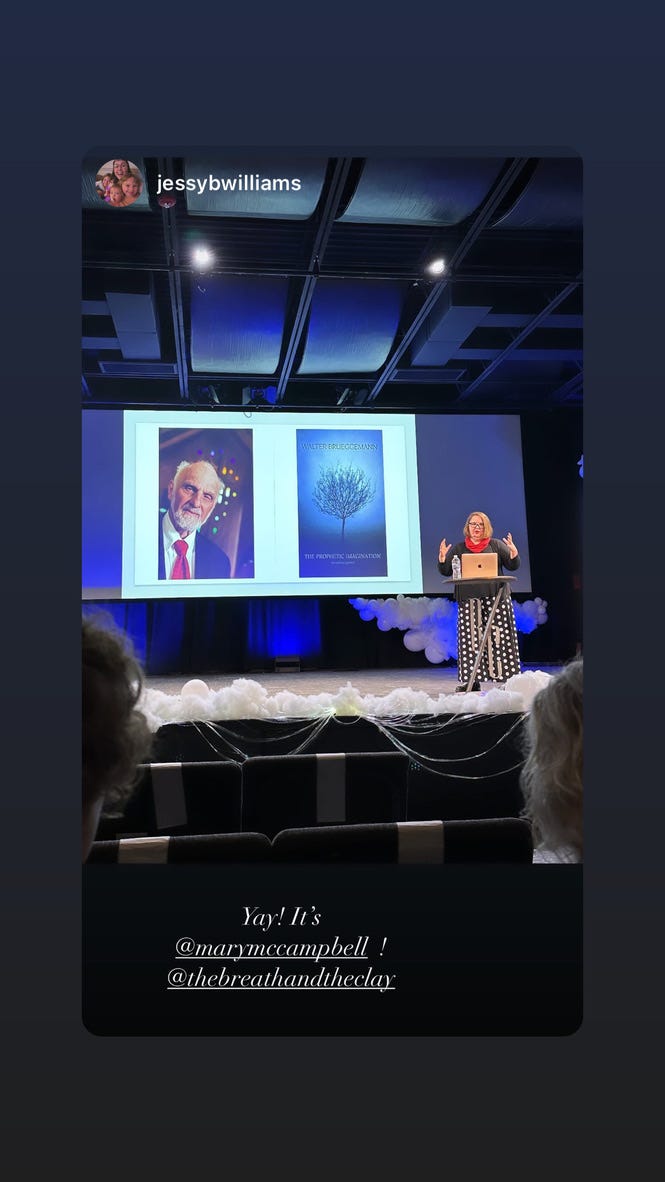

I have been to many very good arts and faith focused conferences (I will write another post on that in the near future). But I have never been to one that was so diverse (racially diverse, arts-form diverse, age-range diverse) and so boosted by an underlying reality of joy and wonder. The short keynote presentations were indescribably good. I do not know if I have ever been to a conference–academic or arts-based–that did not include a dry, boring, or pretentious presentation. The lineup of incredible presentations were truly an anomaly! While these presentations were truthful as they addressed the painful stuff of reality, there was never a spirit of mockery or cynicism.

I sometimes find that Christian arts environments lack all the levels of diversity named above, that the types of art discussed and practiced feel prescribed, fitting a particular mold. And even if I like the form of art that is the focus, I want to see what boundaries can be pushed, what is new and subversive and weird and childlike (not childish–there is a difference).

Roach sees The Breath and the Clay as a “refuge for artists” and a “safe place to have more questions than answers, a safe place to be in process.” He sees this gathering as a community that shares a “lack of fear around making mistakes and messing up” and a space in which people truly connect in their love of art and God.

If you are reading this and longing for a community of Christ-loving creators, please join us this year! Are you a lover of the arts who wants to sit, listen, and learn?Are you a painter? A musician? a filmmaker? A writer? JOIN US!

Here are just some of this year’s speakers and performers:

I also want to mention that I am THRILLED to give a workshop this year with my dear friend, Dr. Joe Kickasola:

Imagining Our Enemies as Ourselves: How Art Shapes Empathy with Mary McCampbell and Joe Kickasola

Our malnourished capacity for empathy is connected to an equally malnourished imagination. This is especially true when it comes to the Christian imperative to love our enemies. To truly love and welcome others, we need to exercise our imaginations, to see our neighbors more as God sees them than as confined by our own inadequate labels. We need stories that can convict us about our own sins of omission or commission, enabling us to see the beautiful, complex world of our neighbors as we look beyond ourselves. In this workshop, Mary McCampbell and Joe Kickasola will discuss how the arts can expand our imaginations in the direction of love and, in so doing, embolden our ability to rehumanize even our enemies.

As always, thanks for reading! My next newsletter will be on the topic: “Is empathy a sin?”.

.

This idea of an "idol of uncertainty" and that artistic creation may push against that seems like a rich vein. I haven't seen the movie yet, but the line from <i>Conclave</i> that got quoted more than once last night: "If there was only certainty and no doubt, there would be no mystery. And therefore no need for faith."

I wonder what you all may do with your essays in my substack titled: Only Humans Can Be Saved!, Jesus, Jesus, Jesus! There’s just something about

that name., The Holy Spirit? They deal with the growing literature ofn consciousness as something all things have in heaven and earth. I suggest in the first that God is the universe as the overarching consciousness. May not be the best rendering. E.g. how might a modern thinker in this mode paint Michael Angelos God reaching out to touch man?